Like a ‘Shearing Shard of Glass’

In recognition of the Christmas and New Year’s holidays, some of The University of Kansas Health System’s offices will have modified hours on Thursday, December 25, and Thursday, January 1.

November 30, 2018

Christel “Christi” Benz spends her time like many of us – working, traveling and spending time with family. And occasionally she may soak in a hot tub, water her garden or simply splash her face with cool tap water.

Yet she had no idea these ordinary water activities carried a serious risk until doctors discovered she had a rare infection caused by Acanthamoeba.

Acanthamoeba is a microscopic single-cell organism that can infiltrate the body and cause infection to the eyes, skin and central nervous system.

"Acanthamoeba are everywhere," Christi says of the living creature that exists in water and soil environments around the world. "I have no idea how I got it." Learn more about acanthamoeba at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Stuck in a room with closed blinds and a covered alarm clock, Christi fought pain pulses across her eye and facial nerves, feeling like "a shearing shard of glass" on her face. That's when Christi’s husband called the experts at The University of Kansas Health System Eye Center.

"They said I could get in for an appointment the next day," Christi says. "But when I told them everything I saw was in black and white, they wanted to see me right away."

Anne Berenbom Wishna, MD, a cataract and comprehensive surgery ophthalmologist at The University of Kansas Health System Eye Center, and her team immediately suspected Acanthamoeba.

"The hallmark of Acanthamoeba is pain out of proportion with exam findings," Dr. Wishna says. "Christi was in severe pain – she was wearing a large floppy hat and dark sunglasses because her sensitivity to light was so extreme."

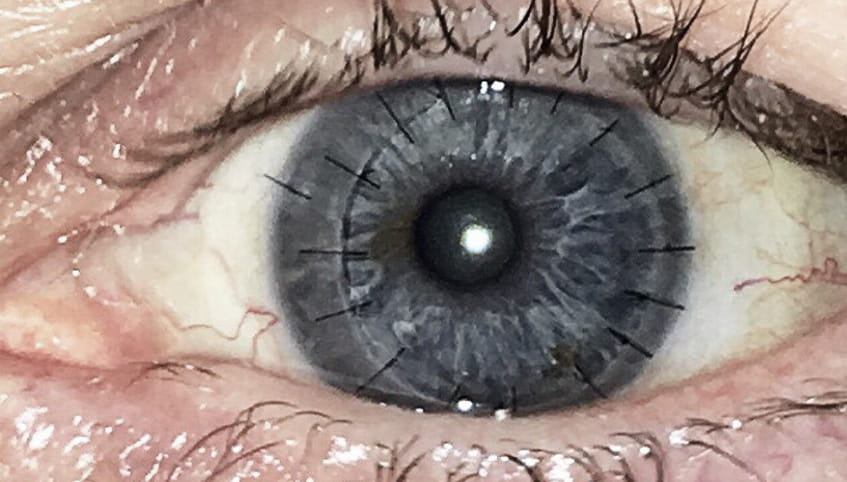

The team was able to confirm their suspicions by examining the eye with a confocal microscope. This high-definition, high-magnification microscope looks directly at the cornea. The health system's comprehensive eye care program is one of the few in Kansas with this technology.

"We were able to see the typical 'double-walled cysts' that are seen in Acanthamoeba," Dr. Wishna says.

Christi had been unknowingly feeding the organism, developing a double-walled cyst for up 14 days before the diagnosis. During that time, she had taken a trip from California to Florida and visited general optometrists, who prescribed steroids. Most eye doctors rarely encounter Acanthamoeba.

"Steroids are like a food for Acanthamoeba," Christi recalls. "So they didn’t help."

Dr. Wishna and her team contacted their corneal and external eye disease expert, ophthalmologist John Sutphin, MD. With experience treating approximately 400 cases of Acanthamoeba, Dr. Sutphin and the eye center team developed a plan to start treatment immediately.

They recommended high dosages of medications to centralize the Acanthamoeba.

"Centralizing the Acanthamoeba improves the possibility of a surgical cure," Dr. Sutphin says. "It also keeps the amoeba away from the sclera, an area that has limited defense to Acanthamoeba invasion."

Christi's eye was finally able to effectively fight back against the double-walled cyst. However, the eye then developed an ulcer.

"It was horrid," Christi says.

With the Acanthamoeba centralized to her cornea and the ulcer putting her at risk for more complications, Dr. Sutphin performed surgery. Christi received a partial cornea transplant, also known as deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK).

"Most patients like Christi haven't realized that their problem might have a surgical solution," Dr. Sutphin says. "DALK is a partial transplant, leaving the deepest layer of cornea. This is the barrier to the amoeba getting into the eye and the target for rejection with full-thickness transplants."

After more than four months of missing work and celebrations due to a closed, painful eye, Christi was able to wake up once again without pain. However, her vision in the once-infected eye is now limited.

"I was able to visit my daughter in St. Louis, visit a brewery and do all these things I hadn't done for months," she says.

Over the next year, Christi will use a topical immunosuppressant and be monitored for recurrence. Her care team will also determine whether her limited vision can be improved with corrective lenses or additional surgical interventions.

As for now, Christi is heading off to Hawaii.

Become an eye, organ and tissue donor at national and state registries or through the Department of Motor Vehicles. Learn more about cornea transplant at restoresight.org.

*Source EBBA.